How do whānau make long term changes that slash rates of violence and abuse in their communities? How do they know if they’re on the right track?

Social scientist, Dr Cristy Trewartha has been asking big questions like these for much of her career.

For the last 15 years she’s been a practitioner, funder, researcher, and academic working in the area of family violence prevention. In 2020 she completed a doctorate focused on ‘Community Mobilisation’ as an approach to foster large-scale change.

Recently, she furthered this thinking in a journal article published in the April 2020 edition of Psychology Aotearoa. In it, she explores connections between Community Mobilisation and the kaupapa Māori approach of E Tū Whānau.

Comparing approaches to mobilising change

Dr Trewartha considers these different approaches using He Awa Whiria, the ‘Braided River’ metaphor developed by Dr Angus Hikairo Macfarlane, and increasingly used by other Māori academics and researchers. He Awa Whiria describes two equally strong knowledge streams which flow beside one another with distinctive autonomy, but also intersect at various junctures, creating opportunities for learning.

“Western evidence on community mobilisation is fairly new, while the kaupapa Māori approach used by E Tū Whānau draws on long-held knowledge about wellbeing. They both take a collective approach and when you bring them together, a space of learning opens.”

She says the western approach defines what to do to mobilise communities, while kaupapa Māori knowledge goes further. It provides guidance on how to mobilise whānau to make changes.

“Tikanga Māori already encapsulates all the things needed to stop family violence.”

She offers wānanga and marae-based hui as examples of how to build awareness of family violence, and how to mobilise change within holistic and supportive traditional processes.

“Creating space where we can really talk about these issues and learn and grow together is key. These collective processes also build leadership and social cohesion which are so important.”

E Tū Whānau’s strategy for mobilising change

Both kaupapa Māori and western approaches place a premium on developing community leadership to create sustained change around complex and entrenched issues, like community and domestic violence.

Dr Trewartha notes that E Tū Whānau’s strategy of using natural leadership structures at all levels and developing kahukura or community-identified leaders who work for, and with, their communities, successfully mobilises people for change.

Other factors, like supporting whānau to achieve their aspirations, and building their confidence also sustain change.

“A determined focus on building strong whānau, rather than on violence within whānau, means that E Tū Whānau is often associated with whānau wellbeing rather than violence prevention.”

Drawing on existing cultural knowledge and strengths is pivotal to this kaupapa.

“When putting Mātauranga into practice, E Tū Whānau gets to the real lived experiences of whānau – ‘what does this look like, feel like, what supports or blocks change.’”

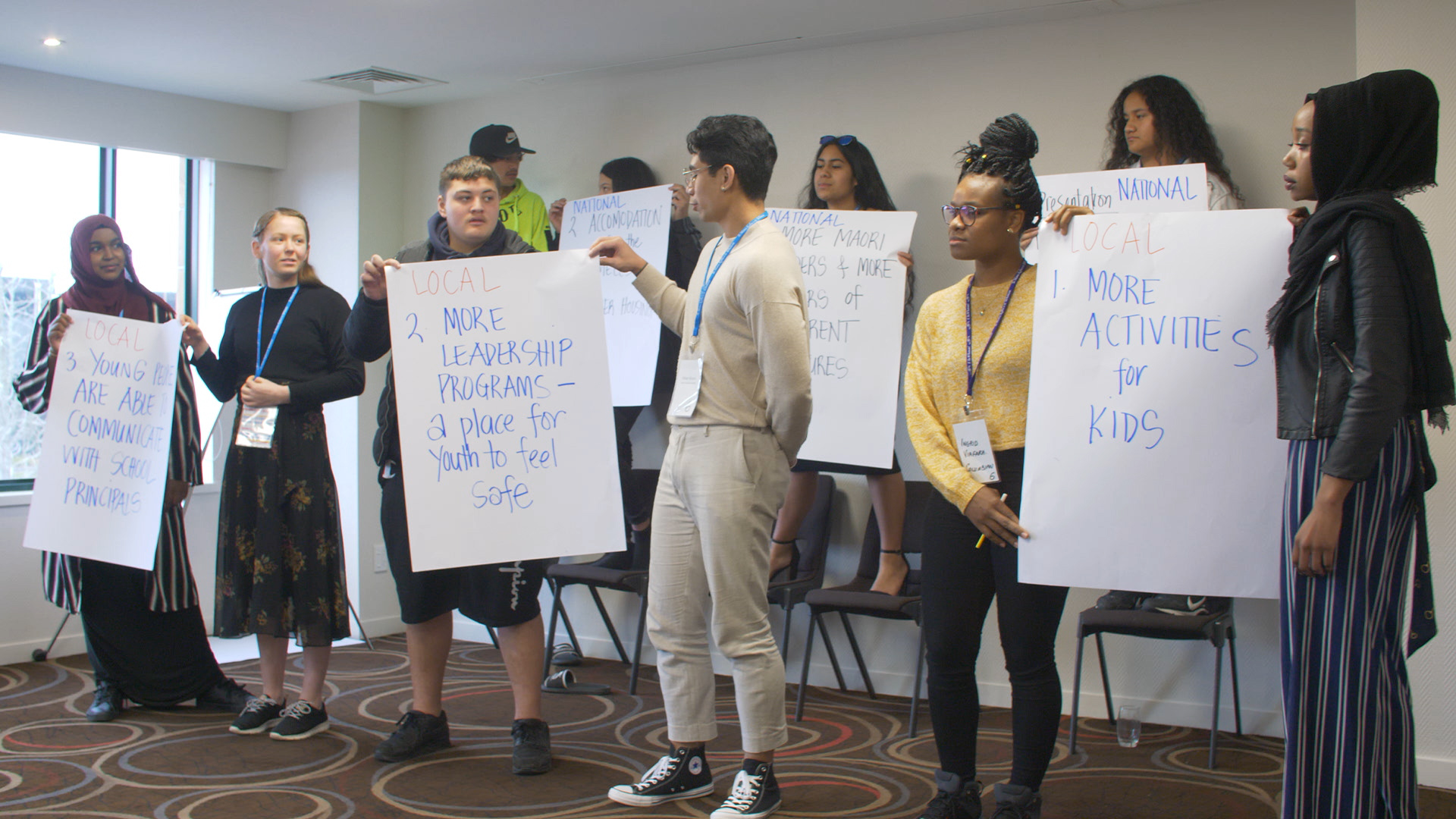

Mobilising refugee and migrant communities for change

Dr Trewartha says that evaluations of E Tū Whānau show that the approach also works for refugee and migrant communities because it reconnects people with their heritage, develops an appreciation of kaupapa Māori and recognises shared experiences of colonisation and racism.

“While E Tū Whānau is uniquely Māori, it is broadly consistent with international evidence on reducing family violence in indigenous communities. It points to building deep trusting relationships that mean people can really talk about what’s happening in their lives with their whānau and their communities. Others are now looking at E Tū Whānau to see how it works.”

Sustaining meaningful change

Dr Trewartha is one of a growing number of researchers interested in communities ‘mobilising’ to create lasting change for members and the process that supports this. She is clear that sustained change is more likely when it is initiated by a community working in equal partnerships with practitioners, funders and, what the mainstream would see as, ‘experts.’

She identifies what lies at the heart of this partnership for E Tū Whānau.

“The E Tū Whānau kaupapa uses Te Ao Māori values and approaches. It starts with what is tika, what is right, and then uses an iterative process which allows communities to learn as they go. This is the right approach for working with complex problems like family violence.”

Until now, she says, most evidence-based information on how communities make positive changes and solve their own problems has been anecdotal.

“The stories people tell about their lives and experiences are really important sources of information. We also need objective measures and data that we can use to track change over time and assess the impact of different strategies. This helps us to know if and how change is happening, and what is needed to inform policy and decision making. This work is emerging and is very exciting especially for entrenched issues like family violence.”

Read Cristy’s full article in Psychology Aotearoa May 2020 (pages 16-22) here.