Wāhine and tāne Māori are unlocking a powerful healing connection to te ao Māori through Te Ara ki Hawaiki Roa, a series of wānanga combining neuroscience, the social history of pre–European Māori family life, and traditional practices that kept women and children safe.

Te Ara ki Hawaiki Roa is designed and delivered by the National Collective of Independent Women’s Refuges (NCIWR) National Office with support from E Tū Whānau.

Over 200 Women’s Refuge kaimahi and whānau have learnt through these wānanga that their tīpuna lived in a world where violence within the family unit, between wāhine and tāne, or directed at tamariki, was not tolerated.

The wānanga series started as in-house courses on tikanga and te ao Māori for Women’s Refuge kaimahi so that they could better-support Māori whānau using their services.

Maria Burgess is Te Roopū Whakawhanake (Māori Development Team) Manager at Women’s Refuge, National Office.

“The content of these wānanga was so effective that we decided to offer them directly to whānau associated with Women’s Refuge – men and women who were starting their own healing journey within te ao Māori,” Maria says.

Science and mātauranga Māori can keep whānau safe

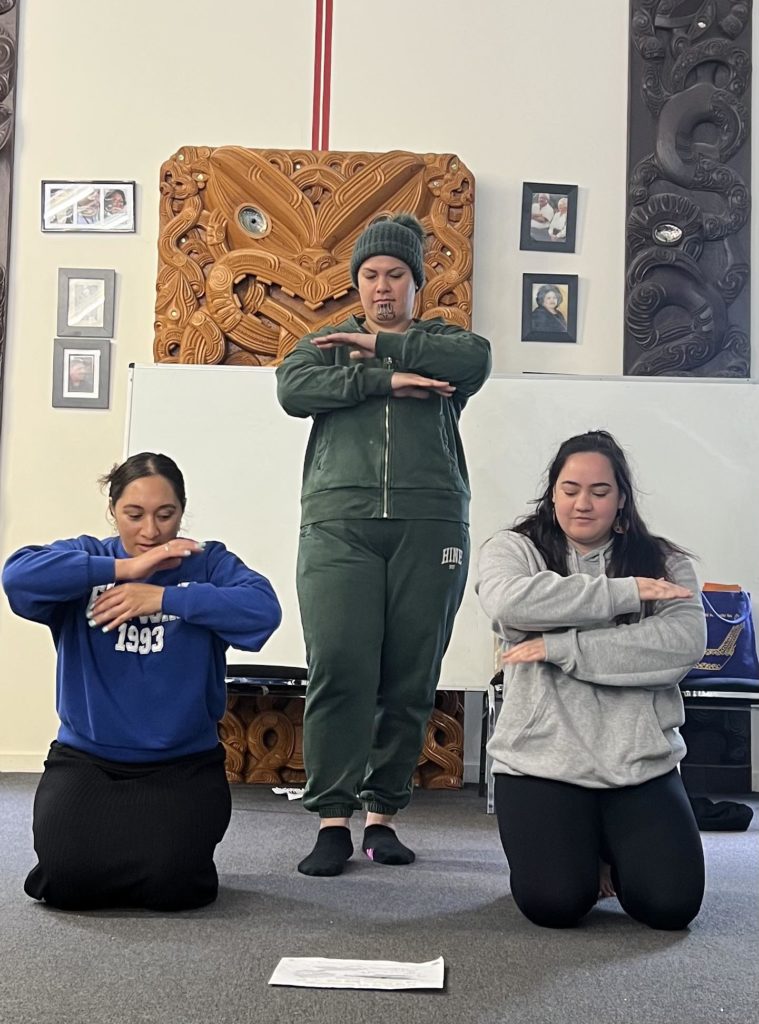

Maria and her colleagues, Diane Woodhouse and Jahneal Chapman, designed Te Ara ki Hawaiki Roa wānanga to include rongoā, mirimiri, maramataka and other forms of mātauranga Māori. The content highlighted the strong links between traditional practices and contemporary science.

Guest facilitator Patrick Salmon introduced whānau to pūrākau, the traditional practice of sharing ideas and passing down knowledge through the stories of tīpuna and atua and the values they held dear in pre–European Aotearoa.

“By using pūrākau,” Jahneal said, “Patrick educated participants about what day-to-day life was like for Māori, before colonisation and land loss, before the introduction of alcohol and the intergenerational trauma that came out of it.”

Deb Rewiri from the Brainwave Trust introduced wānanga participants to the science of brain development and the growing body of evidence on how domestic violence affects the minds of young children.

She shared scientific evidence on the positive effects of kōrero awhi and general non-violent, respectful behaviour between family members.

“Deb linked it to what the earliest missionaries wrote about Māori. They described them as peaceful people who practised the most respectful child rearing techniques they had ever seen.

Tamariki were not hit. You weren’t allowed to hold your tamariki if you were grumpy or having a fight because they knew that energy would transfer to the pēpi. You weren’t even allowed to work the garden if you were angry for the same reason,” says Jahneal.

Proud to be Māori

Maria and her team have forged ongoing, supportive relationships with Te Ara ki Hawaiki Roa participants.

“We keep in touch with everyone. We listen to their feedback and do whatever we can to awhi them through their healing journey,” she says.

Participants talked overwhelmingly of how the kōrero about their tīpuna and their culture became a huge source of pride and personal self-esteem.

“I see such change in the wāhine especially. Most wouldn’t speak for the first couple of wānanga. They just sat there listening, soaking it all up. Then, wow, they’re now engaged, talking and thirsting for more information.

They’re sitting in their mana, and they are proud to be who they are, proud to be Māori,” says Diane.

Te Ara Ki Hawaiki Roa – In their own words

Thirty-one-year-old Oceana has six tamariki. A solo mum from gang-affiliated whānau, she’s been clear of methamphetamine addiction for three years but rarely speaks to anyone about the experience.

“I didn’t learn anything about te ao Māori growing up except for a few words of te reo in school so it was all new to me.

But something about the kōrero built up my confidence so that I could speak about what I’d been through in my life.

These wānanga have given me a lot of motivation. They’ve given me tools to use in my life. Tools that help me calm down when I get really agitated, that help me with my kids.”

Jacqueline is a shy, stay at home solo mother of eight tamariki and two moko.

She had a rural, te ao Māori upbringing but says it was ’bashed out of her’. This is the first wānanga of any kind she has been offered.

“My life was kinda ugly. I was at home all day, stuck in four walls. Just turning up to the wānanga was nerve racking. I didn’t know what to expect but socialising with other people broke me out of my comfort zone, out of my shell.

It’s [wānanga content] drew a lot of stuff up from inside me, stuff I’d pushed under the carpet. The trauma is still there and I’m still figuring a way through and learning to self-heal.

I understand now that my children have been affected by my trauma. It’s made me step up and now I’m learning and healing, along with my children.”

Justin has had childhood trauma, addiction and anger issues to deal with.

He admits to being intimated by doing his first wānanga in a wāhine-dominated space but his wife, ”my biggest cheerleader and critic”, encouraged him.

“It’s been an eye-opener. It’s helped me reconnect with my partner and whānau and understand what our wāhine really go through. Stuff happens behind closed doors but listening to these wāhine made me understand how much maemae my wife was holding.

[Being with these wāhine], I now understand how how important it is to heal together.

Our people need te ao Māori to heal. The knowledge about atua Māori and those stories that Pat shared have helped me teach my tamariki about important values that can keep them safe.

I connect so much better with my son now.

It would be amazing if more tāne could come on this wānanga.

But tāne won’t come unless they see change. If they see me changing, hopefully my friends and whānau will see that they can learn and change too.

[For us], te ao Māori is the way of the future.”

Kiri works with whānau on a large urban marae and is often the person others go to for advice. Despite losing two close whānau in the last year, Kiri’s life seemed to be on track. Turns out she wasn’t the functional recreational drug user she’s told herself she was.

”I got a short sharp shock.

I thought I was going to these wānanga to get me more tools to help others. Instead, I had to face my own truths.

I was in a dark place, physical, mentally and spiritually but I’d kept it all in.

Different facilitators brought us different types of mātauranga, different kai for the soul. We all took what we could handle at the time knowing we were safe under the korowai that Di, Maria and Jah placed over us.

Learning about the different stages of te pō helped me grieve the passing of my father and a moko, and the separation from my husband.

Through these wānanga, I realised that that I was a dysfunctional wahine living in a functional world.

It’s still hard but having genuine conversations with these wāhine and tama in a te ao Māori space has allowed me to get to a place where it’s safe to talk about my issues.

Another great thing about this wānanga is the ongoing support from the whānau we have built. I feel I can ring or text anyone and say, ‘I’m not coping’ and they’ll be there for me.”

Rowena is the national coordinator for NZ P-Pull, the grass roots nation wide movement that supports whānau affected by methamphetamine.

“I’ve been supporting wāhine through their struggles for years but this wānanga has really amazed me.

I saw so many shy wāhine step into a space and grow into confident women. They know who they are and know they belong to an amazing culture. They’re proud of it. Seeing them share their thoughts and ideas with the group is incredible.

I’m Māori so it’s been huge for my personal development too.”

Want more?

Read how violence within whānau is not traditional and Our Ancestors enjoyed loving whānau relationships within which everyone was safe and valued.

Read about the growth of P-Pull, the nationwide movement for whānau impacted by methamphetamine.