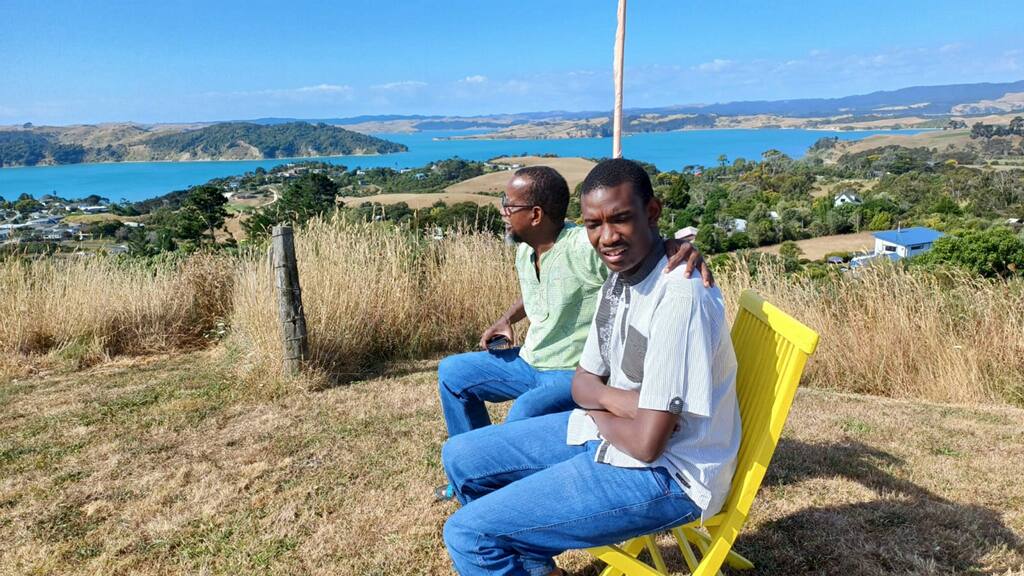

Mustafa Farouk has a 21-year-old son with autism. His friend, Abdirizak Abdi, has three neurodivergent children. One has been diagnosed with Aspergers Syndrome. Two others are autistic.

In the eyes of these two stalwarts of the Waikato Muslim community, all their children are a blessing but it’s their challenging, beloved autistic children who are ‘noor’, meaning ‘light’ or ‘illumination’ in Arabic.

“These children are a light in our lives. They illuminate the path that shows us a way to support them and all our whānau,” says Mustafa.

Mustafa and Abdirizak are acutely aware of the complicated, lifelong challenges families face in caring for these special rangatahi, including the increased likelihood of family distress. They’re also alert to the differing views and levels of knowledge held by others in their spiritual community.

Increasing opportunities and connection

Inspired by the way E Tū Whānau supports whānau, hapū and other community groups to address their challenges collectively, the two friends helped establish Autism Noor two years ago. Based in Hamilton, this parent-to-parent support group is for Muslim whānau with children on the autism spectrum.

Their members, who include tangata whenua and pākehā reverts (those who convert) to Islam, are from a variety of cultures.

Some include their special needs rangatahi in all aspects of family and community life. They attend a special needs school and are regularly monitored within the health system. Where practical, they are also part of Waikato’s active Islamic community.

Other families are not so open, nor are they as well informed.

Abdirizak, an educationalist who left his native Somalia when he was 20 years of age, had never heard of autism before leaving home. This is despite an apparent prevalence of the condition within Somali society and in parts of the Somali diaspora.

“People with autism were just regarded as crazy or foolish. Families isolated their child out of embarrassment, ignorance or fear. Those fears are still held by a few in our community,” Abdi says.

Autism Noor offers spiritual and practical support modelled on the six E Tū Whānau values

Currently up to eleven families are actively involved in Autism Noor.

They pool their resources, hold regular, informal meetings and share accurate and up to date information about autism.

“We bring our lived experience and shared Muslim values and beliefs to the group to better support each other through some of the more challenging times,” says Mustafa.

Their autistic rangatahi are all individuals with different abilities and needs. Sometimes these needs are acute, and parents and siblings are their first, most important and most dedicated carers.

“It’s not easy, especially for my wife who is at home with our children when I’m at work, but we love our children. They’re unique and have wonderful ways of being in the world,” says Abdirizak.

Mustafa is currently gathering material for a series of resources modelled on the E Tū Whānau values booklets to help Muslims understand autism from a spiritual perspective.

Mustafa says there is little information about autistic people specifically, but Islamic beliefs provide a strong foundation to start from.

“Supporting vulnerable and less fortunate members of our society is one of Islam’s most important values. We believe that everyone has been created by Allah for a purpose, that individuals with disabilities have a special place in society and that all children should be treated with kindness, compassion, and respect, regardless of their abilities or disabilities,” he says.

“Our kind, caring children are innocent in the eyes of God” says Abdirizak, “and it’s our job to look after them.”

Autism Noor is already having impactful spinoffs.

Access to African members of the group has enabled an AUT Master’s student to include their experience in his thesis on the experience of disabled members of Aotearoa’s African community within the health system.

A Waikato University student who did a literature review of Islamic and Arabic sources on autism used that experience to get a job in Nelson working with disabled whānau.

Want more?

Autism Noor can be contacted through Waikato Muslim Association or by ringing 021 182 5262.

Read about the inclusion of former refugee and migrant communities within E Tū Whānau.

Learn more about the journey of E Tū Whānau, which came out of a national summit in 2008.