Communities throughout Aotearoa are coming together at wānanga to look honestly at issues facing their whānau and to work together to find their own solutions. They’re using the E Tū Whānau kaupapa with its focus on traditional Māori values at these wānanga.

Whanaungatanga and frank, heartfelt kōrero were shared, with aroha at a weekend E Tū Whānau wānanga held recently at Pouakani Marae in the South Waikato town of Mangakino.

The wānanga was the third in a series facilitated by Ngāti Kahungunu ki Wairarapa General Manager, PJ Devonshire, and his partner Pania to discuss actively applying the E Tū Whānau kaupapa/Maori values in each community.

The wānanga was the third in a series facilitated by Ngāti Kahungunu ki Wairarapa General Manager, PJ Devonshire, and his partner Pania to discuss actively applying the E Tū Whānau kaupapa/Maori values in each community.

Pouakani Marae

The Pouakani Marae whānau descend from Ngāti Kahungunu ki Wairarapa iwi members who left whānau in the Wairarapa in the 1940s to develop land allocated to them in recompense for the loss earlier in the century of much more valuable whenua around Lake Wairarapa. After World War Two they broke in the land, cleared the scrub and bush and turned the whenua into farms. The township of Mangakino was also built on whenua given to the people of Wairarapa.

Addressing the whānau who had gathered in Tamatea Pokai Whenua, the marae’s beautiful new Whare Tīpuna, PJ gave a brief rundown of the tribe’s history. He talked of the need for the Wairarapa whānau to awhi their Mangakino cousins.

“Back in the day, mum and dad would bring kai moana up here, paua and crayfish from the Wairarapa coast, aroha from home, and we need to do that again. Our connections are still strong.”

Pointing to ancestors depicted on carved pou within Tamtea Pokai Whenua, PJ reminded whānau that theirs was the only Ngāti Kahungunu ki Wairarapa marae containing all the iwi’s noteable tīpuna.

“The past is alive in this house,” he said.

Happy healthy whānau the goal

The 25 whānau who gathered at Pouakani Marae for the weekend had a strong vision for their community. They want all their whānau to be happy, healthy and functioning well and were keen to brainstorm practical ways to support that goal.

The 25 whānau who gathered at Pouakani Marae for the weekend had a strong vision for their community. They want all their whānau to be happy, healthy and functioning well and were keen to brainstorm practical ways to support that goal.

The whānau were inspired by PJ’s tales of the last sitting of the Māori Parliament and the Kotahitanga Movement hui which was held at Papawai Marae in Greytown in 1898. Noelene Reti, who along with Memory Te Whaiti belongs to the core group of highly motivated whānau who organised the wānanga, believes that unity is an important goal for the whānau.

“Maybe we could work towards bringing our people back together again under one umbrella. We need a new kind of Kotahitanga movement for the safety of our moko, our tamariki, our iwi. It’s an obligation we have from Mana Atua to our mokopuna,” she says.

Older whānau members remembered shared holidays and suggested reinstating regular weekend sporting competitions between rugby and netball teams from different branches of the tribe.

Others emphasised the importance of opening all meetings with whakawhanaungtanga so that everyone would know how things were with each other and were therefore more likely to know when to help those who needed it.

Sharing wealth was another idea canvassed. It was normal to fundraise for a new building but why not, said someone, fundraise for scholarships to allow young people access to higher education.

Facing problems head on

The Pouakani Marae whānau are taking practical and determined steps to strengthen their community, but they don’t shy away from their problems.

Like other rural communities, they’re grappling with high unemployment, isolation, a strong gang presence, alcohol and drug abuse and, as indigenous New Zealanders, the ongoing consequences of colonisation.

Noelene Reti with a photo of her great grandmother Hinehuirangi Hutana, also known as Mini.

It’s not about the blame game,” says Memory Te Whaiti. “It’s about understanding our history, the good and the bad, and decolonising our way of thinking. It’s about valuing the strength of our own tīkanga. Then we can build an honest and healthy future going forward.”

Both Noelene and Memory were raised in Mangakino and have children and mokopuna there. Their moko are the seventh generation living in the area since their tīpuna migrated to Mangakino.

They were both brought up traditionally by their nannies but they know that’s not how many of their relatives were raised.

Noelene’s daughter, Hinehurangi Dick-Reti, who came along to the wānanga with her tamariki and pepe, spoke of her sorrow and anger at the damage the drug ‘P’ is having on others of her generation.

“I am the eldest of my grandparents’ mokopuna, and my son is the eldest in his generation. I feel that I have a responsibility to ensure our children are brought up in a safe, drug free, violence free whānau.”

Wilma Kingi said that for her, the focus of the wānanga was on strengthening and empowering the rangatahi.

“The kids are open to change, they want a bettter future; the hardest part is getting their parents on board.”

Reconnecting whānau members

Nineteen-year-old Brandon Martin came along to listen and help with the tamariki.

“I’ve been away – Auckland, ‘Oz’, all over. It’s great out there but it’s great to be home. I reckon some of the farmers here need a hand. I’m pretty fit for that.”

James Wairuku Pedersen and Quanita Robinson-Russell reconnected at the wānanga. They hadn’t seen each other since primary school. Quanita Robinson-Russell is a mother of four and grandmother to 17 moko and three great grandchildren. She’s doing everything she can to change her mokos’ lives for the better.

Unlike other wānanga participants, Quanita is part of the iwi’s Lake Ferry community. She knew little about her relatives in Mangakino until she attended a Ngāti Kahungunu ki Wairarapa E Tū Whanau wānanga at her own marae at Kohunui.

Quanita lost a leg trying to stop a confrontation between some of her moko and their cousins from rival gangs. Despite that, she drove on her own all the way from Pirinoa to Mangakino because she believes that the kaupapa of this series of wānanga can help her guide her whānau away from senseless violence. She’s just as passionate about getting to know her Mangakino whanaunga and sharing her knowledge of their joint whakapapa.

Quanita and 70-year-old James Wairuku Pedersen, father of four with12 moko and one great grandchild, discovered that they shared great grandparents. They had also attended Pirinoa Primary School together when they were small tamariki.

“It’s a real joy to see Quanita here,” says James as they both pour over old books, photos and whakapapa charts, laughing and making connection after connection.

“I was whangai at an early age, but came back to my own parents here in Mangakino when I was seven and I lost touch with everyone back in the Wairarapa. I grew up, worked on farms around here, and spent years with my own family overseas. Now that I’m retired, I am back and finding these wonderful links. It’s like we’ve planted a seed and this lovely plant is growing,” he said.

“I was whangai at an early age, but came back to my own parents here in Mangakino when I was seven and I lost touch with everyone back in the Wairarapa. I grew up, worked on farms around here, and spent years with my own family overseas. Now that I’m retired, I am back and finding these wonderful links. It’s like we’ve planted a seed and this lovely plant is growing,” he said.

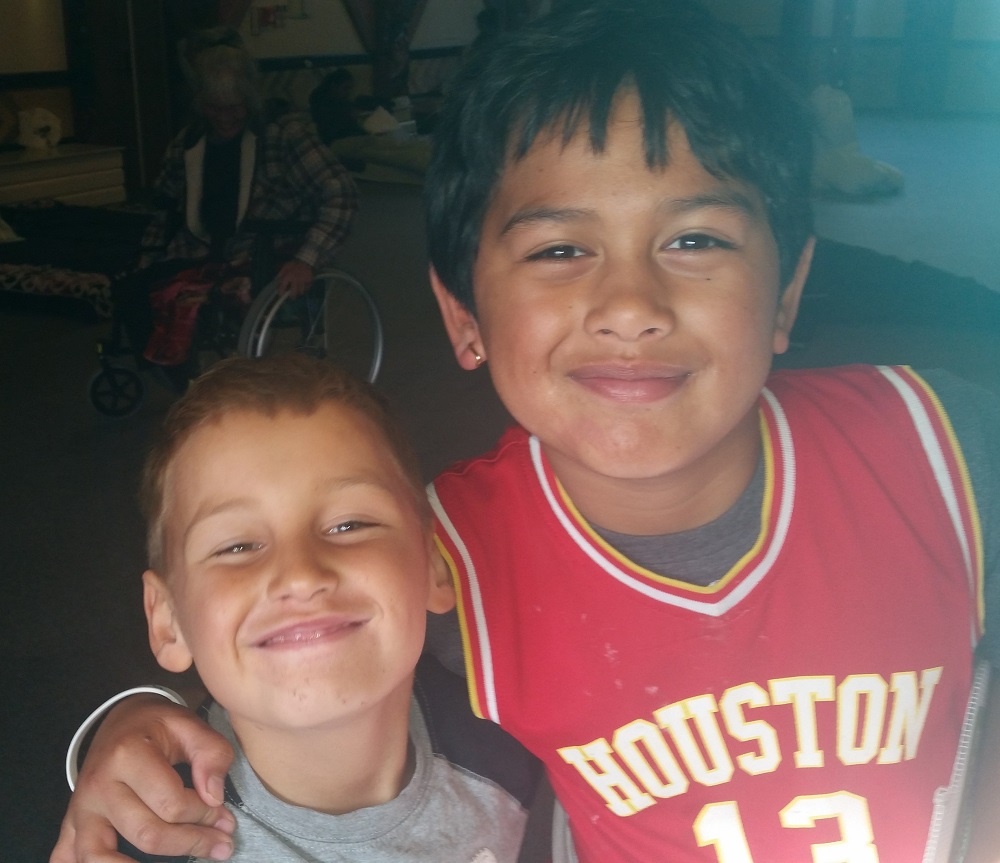

“I love seeing the faces of those who have passed in the faces of the young,” says Quanita. “There’s always one moko who looks like your mum or dad, an uncle or koro.”

“Looking at the faces of our tīpuna, it makes me realise what a great thing it is to be part of a generation and to have children and moko of your own. We shouldn’t underestimate this. You can’t get by without your family.”